Regular attendance at a medical fitness facility prolongs life, decreases hospitalization

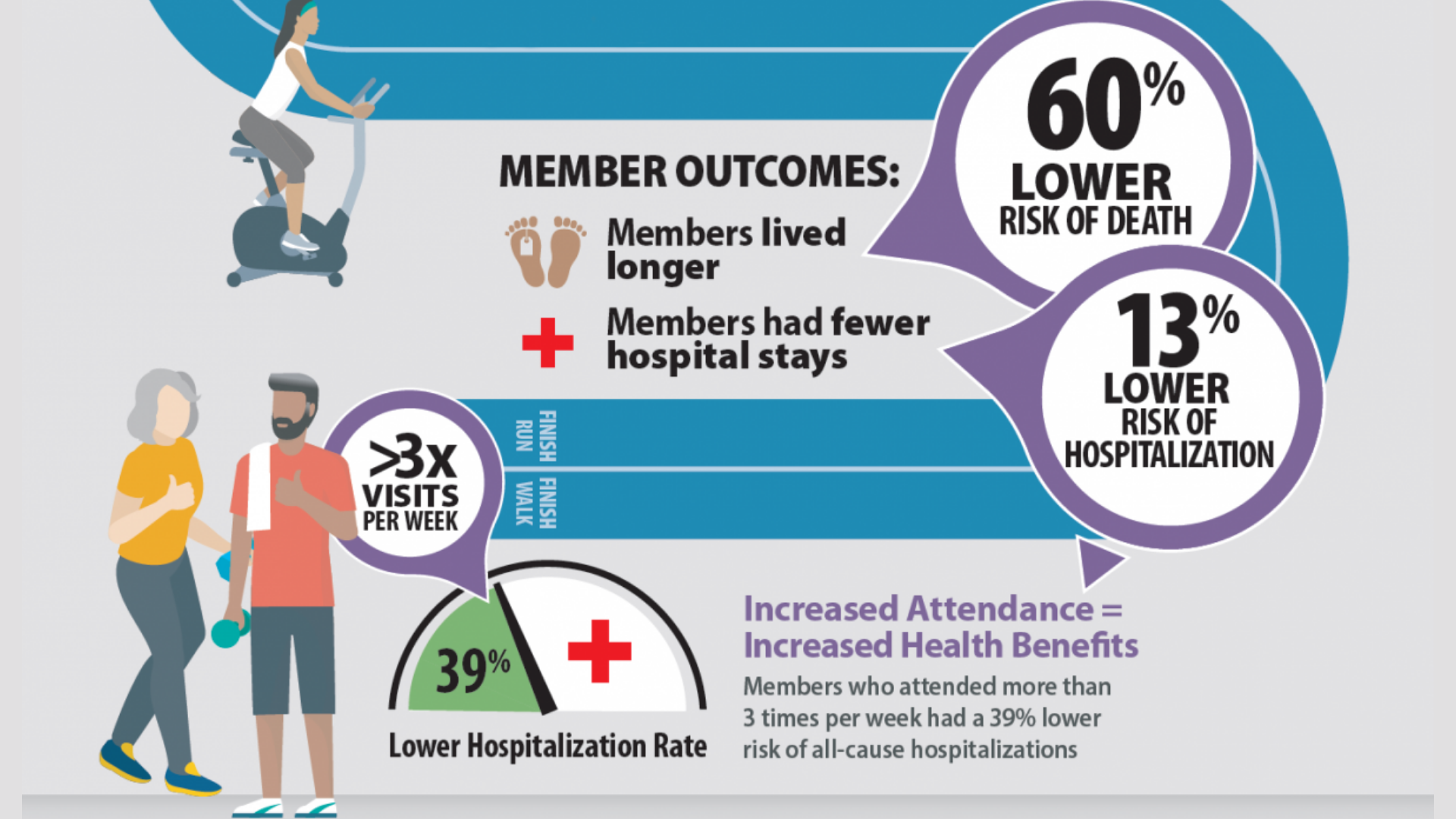

Belonging to a certified medical fitness facility like Winnipeg’s Wellness Institute or Reh-Fit Centre lowers a person’s risk of dying by 60 per cent, compared with a similar person who does not attend such a facility, new research shows.

Members also have a 13 per cent lower risk of being hospitalized, the 10-year retrospective study found.

And members who attend a medical fitness facility more than three times per week exhibit even better health, with a 39 per cent lower risk of hospitalization.

The study, published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, is the first to examine the long-term health outcomes of those who attend a medical fitness facility, versus those who don’t.

The project was conducted by researchers at the Chronic Disease Innovation Centre (CDIC) at Seven Oaks General Hospital and the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (MCHP) in the University of Manitoba’s Rady Faculty of Health Sciences.

“It’s exciting to see this dramatic evidence, based on a large population over a 10-year period, of the benefits of joining a medical fitness facility in preventing disease and premature death,” said Dr. Alan Katz, professor of family medicine and community health sciences, and director of the MCHP.

“These findings provide guidance for health management, and we hope they will inform health policy.”

The Wellness Institute at Seven Oaks General Hospital and the Reh-Fit Centre in South River Heights are not-for-profit facilities that offer a broad range of health, wellness and disease rehabilitation programs. They deliver evidence-based, medically integrated programming and provide a greater degree of medical oversight than traditional fitness centres.

The study focused on more than 19,000 new adult members of the Wellness Institute or Reh-Fit Centre from the time each started scanning their membership card for entry. Their average age was 47.

Members had access to an annual health assessment, fitness equipment, group exercise classes and certified fitness staff. When members swiped in, they may have been accessing services such as nutrition counselling rather than exercising, the study notes.

Using members’ and non-members’ anonymized personal health identification numbers, the researchers used databases at MCHP to compare members’ health status and mortality rate from 2005 to 2015 with those of a control group of nearly 516,000 people from the general Winnipeg population.

Individuals in the control group were matched and directly compared with those in the member group according to age, sex, income (based on postal code) and health conditions. The level of physical activity in the control group was not part of the study.

The researchers conclude that health-care systems should consider the medical fitness model as a preventive public health strategy to encourage physical activity participation.

“These findings present an opportunity for people to take charge of their health, and for medical professionals and governments to offer a simple option for reducing medical risk,” said Dr. Paul Komenda, professor of internal medicine and research director of the CDIC.

“The medical fitness model holds tremendous potential for public health. Our study found that members tended to be from higher income groups. Imagine if all income groups had regular access to this kind of life-prolonging facility.”

The study received funding from the Seven Oaks General Hospital Foundation, with support from Research Manitoba and the Heart and Stroke Foundation.

View the full infographic of the study findings.